December 11, 2025

This post is a technical deep dive of Phantom, as RISC-V FHE-VM. If you’re not familiar with Phantom we first recommend the anoucement blogpost.

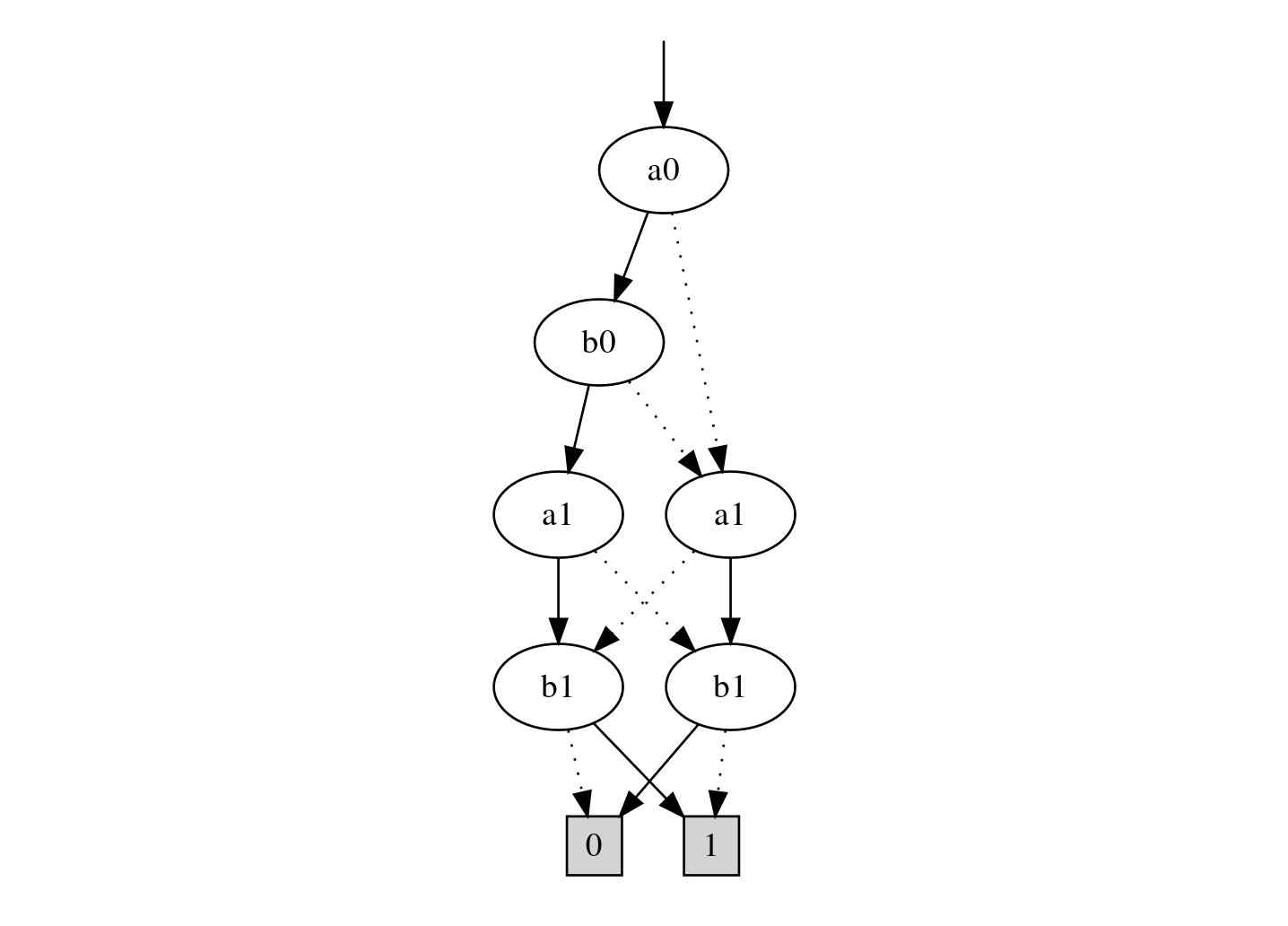

Below is a high level diagram of the Phantom pipeline:

Click for enlarged image

Step 1 is provided out of the box by the rust compiler. Step 2 simply parses the ELF file, decodes the instruction, and encodes the instructions in FHE plaintext polynomials. Step 3 is simple encryption, and step 5 is trivial - send the output ciphertext backt to the client.

Hence, for the rust of the document we will focus on the actual construction of the FHEVM.

A virtual machine consists of 4 main building blocks: ROM, RAM, Registers, and PC (program counter).

ROM is read-only memory and stores the instructions of the program. RAM is read/write long-term storage and is the memory of the program. Registers act as temporary short-lived memory, to prevent constant RAM accesses1. PC tracks the address of the next instruction.

At every cycle, an instruction, addressed by PC, is read from the ROM and decoded. Then the instruction is executed. Execution of an instruction either updates the RAM, PC, or Registers2.

We can categorize the instructions with respect to which of the three (RAM, PC, Registers) they update.

Arithmetic, load and store instructions all have the secondary effect to increment the PC by 4.

Apart from the classic fetch-decode-execute pipeline there are a few additional details specific to RISC-V:

[x0,...,x31], each 32-bits in

size.x0 is always 0 and all writes to

x0 are ignored.To summarize, a cycle:

instruction ← ROM[pc].opcode: type of operation,rd: return register,rs1: input register 1,rs2: input register 2,imm: immediate, a constant hard-coded into the

instruction.x[rd] ← op(x[rs1], x[rs2], imm, pc) and

pc ← pc + 4.x[rd] ← RAM[x[rs1]+imm] and

pc ← pc + 4.RAM[x[rs1]+imm] ←x[rs2] and

pc ← pc + 4.condition, pc ← pc + imm,

else pc ← pc + 4.Here is a small program that illustrates the fetch-decode-execute

semantic. It adds x1 to x2 until

x2 becomes greater than x3 and then stores it

in the RAM:

0x0000: 0x00208133

0x0004: 0xfe316ce3

0x0008: 0x00202023pc = 0x0000: 0x00208133.0x00208133 =

0000000 00010 00001 000 00010 0110011. We have

op = 000 | 0110011 which is ADD, with

rs1=0b00001, rs2=0b00010 and

rd=0b00010.add(x1, x2) -> x2

and set (pc = 0x0004) ← (pc = 0x0000) + 4 .pc = 0x0004: 0xfe30eee3.0xfe316ce3 =

1111111 00011 00010 110 11001 1100011. We have

op = 110 | 1100011, which is BLTU (unsigned

comparison), with rs1 = 0b00010, rs2=0b00011

and imm=sext(0b111111111100) = -4.(pc = 0x0000) ← (pc = 0x0004) - 4 if

x2 < x3 else increment

(pc = 0x0008) ← (pc = 0x0004) + 4.The cycles execution will ping pong between pc = 0x0000

and pc = 0x0004 until x2 >= x3. Once

x2 >= x3 the pc is incremented by the

default value (4), which sets it to

pc = 0x0008. - Cycle n 1)

Fetch instruction at

pc = 0x0008: 0x00202023. 2) Decode

0x00202023 = 0000000 00010 00000 010 00000 0100011, see

from op = 010 | 0100011 that it is SW (store

word), with rs2=0b00010, rs1=0b00000 and

imm=0b000000000000. 3) Execture: store

x2 in the address (x0=0) + (imm=0) = 0 of the

RAM and set (pc = 0x000c) ← (pc = 0x0008) + 4 .

At its core, homomorphic encryption (HE) allows computation on encrypted data: given ciphertexts encoding plaintexts, one can apply certain algebraic operations (e.g. addition, multiplication) to obtain a ciphertext which decrypts to the result of those operations on the original plaintexts.

In GLWE-based FHE schemes, encryption encodes plaintexts as polynomials (or torus-vectors) over a ring and supports addition, multiplication operations and automorphisms.

We work on the Torus \(\mathbb{T}_{1}[X]\), the set of all real polynomials. Arithmetic is performed modulo \(1\) coefficient-wise and modulo \(X^{N}+1\) at the polynomial level.

We denote \(\mathbb{T}[X] = \mathbb{T}_{1}[X]/(X^{N}+1)\) and occasionally refer to \(\mathbb{Z}[X]\), the set of integer polynomials.

The plaintext algebra follows the arithmetic of \(\mathbb{T}[X]\). That is, we can add message together, multiply them by integer polynomials (of \(\mathbb{Z}[X]\)), which includes integer constants and monomials \(X^{i}\). We can also apply automorphisms: map \(X^{i} \rightarrow X^{ik}\), which acts as permuting coefficients (with at most a sign change).

A GLWE ciphertext of rank \(d\) is a tuple \((b, \vec{a})\) with \(b = e + m -\langle a, s \rangle\), where \(\vec{a}\in(\mathbb{T}[X])^{d}\), \(e\in\mathbb{T}[X]\) an error polynomial with small variance, \(\vec{s}\in(\mathbb{Z}[X])^{d}\) and \(m\in\mathbb{T}[X]\).

Decryption is performed as \(b + \langle a, s \rangle = m + e\). As long as \(e\) is small enough, \(m\) can be recovered.

It is easy to see that this encryption is linearly homomorphic over any linear function of the secret key (addition, multiplication by a constant, etc…).

A GGLWE ciphertext is a tuple of GLWE encrypting \(m \cdot \mathbf{w}\) where \(m\in\mathbb{Z}[X]\) and \(\mathbf{w} = (2^{-B}, 2^{-2B}, ...)\) is a decomposition basis. More concretely:

\[\textsf{GGLWE}(m) = (\textsf{GLWE}(m\cdot 2^{-B}), \textsf{GLWE}(m\cdot 2^{-2B}), \dots)\]

This type of ciphertext enables the following operation:

\[ m_{0}\in\mathbb{T}[X] \otimes \textsf{GGLWE}(m_1\in\mathbb{Z}[X]) \rightarrow \textsf{GLWE}(m_0m_1\in\mathbb{T}[X])\]

A GGSW ciphertext is a tuple of GGLWE encrypting \(m \cdot (1, \vec{s})\), where \(m\in\mathbb{Z}[X]\). More concretely:

\[\textsf{GGSW}(m) = (\textsf{GGLWE}(m), \textsf{GGLWE}(ms_0), \textsf{GGLWE}(ms_1), \dots)\]

The GGSW ciphertext format enables a homomorphic operation called the external product:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m_{0}\in\mathbb{T}[X]) \otimes \textsf{GGSW}(m_1\in\mathbb{Z}[X]) \rightarrow \textsf{GLWE}(m_0m_1\in\mathbb{T}[X])\]

We will see that the external product is a crucial operation that is at the core of many higher level homomorphic operations used in Phantom.

Before diving into the individual components of Phantom and technical details, we will go over a high-level overview of its core components.

The VM is composed of four major components:

u32.The ROM, REGISTERS and RAM can all be accessed with the same API: - Read an encrypted value at some encrypted address. - Write an encrypted value at some encrypted address.

Additionally, at each cycle the VM will update one of the following: - The program counter in a non trivial way (instead of incrementing it by 4). - The RAM by storing a value, at an address, read from the REGISTERS. - The REGISTERS by either writing to it a value read from the RAM or writing the result of an arithmetic operation.

The memory for ROM, RAM and REGISTER is structured as a \(32\times \text{\#u32}\) matrix:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} \texttt{u32}_{0, 0} & \texttt{u32}_{0, 1} & \texttt{u32}_{0, 2}&\dots\\ \texttt{u32}_{1, 0} & \texttt{u32}_{1, 1} & \texttt{u32}_{1, 2}&\dots\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots& \vdots\\ \texttt{u32}_{31, 0} & \texttt{u32}_{31, 1} & \texttt{u32}_{31, 2}&\dots\\ \end{bmatrix} \]

In this format, the \(i\)-th bit of

the \(j\)-th u32 is

located at index \((i, j)\). Meaning

that reading the \(j\)-th

u32 can be done by cyclically rotating each row by \(-j\) positions and extracting the first

column. The same can be done for writing, first move the \(j\)-th column to index \(0\), update it, and move it back to its

original index.

This structure is maintained under encryption, execept that columns are batched by groups of \(N\) (the GLWE degree):

\[ \begin{bmatrix} \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{0,0}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{0,N-1}]) & \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{0,N}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{0,2N-1}]) & \dots\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{31,0}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{31,N-1}]) & \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{31,N}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{31,2N-1}]) & \dots\\ \end{bmatrix} \]

As such, accessing the \(j\)-th

u32 is done by first homomorphically cyclically rotating

the columns by \(-j/N\) and then

homomorphically cyclically rotating the first column by \(X^{-(j \mod N)}\). As a result, we have the

bits of the \(j\)-th u32

into the first coefficients of each GLWE of the first column which can

be extracted into an FheUint (see hereafter).

u32Encrypted u32 values can be represented into two

different format, depending on whether the value is used as

data or as control.

| Representation | Ciphertext type | Bits per ciphertext | Phantom type | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Packed data form | GLWE | 32 bits per GLWE | FheUint |

Register and memory (e.g. storage and selection) values |

| Bitwise control form | GGSW | 1 bit per GGSW | FheUintPrepared |

Control bits for addressing, arithmetic, branching, selection |

FheUint — data

representation (GLWE)A 32-bit word is encoded as a single GLWE ciphertext:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m) \quad\text{with}\quad m(X) = \sum_{i=0}^{31} \frac{b_i}{4} X^{(((i\&7)\ll2) | (i \gg 3))\cdot (N/32)} \]

where each coefficient \((b_i \in

{0,1})\) corresponds to one bit of the u32.

For example packing an u32 word into a GLWE with \(N=64\) coefficients looks like

[

1, 0, 9, 0, 17, 0, 25, 0,

2, 0, 10, 0, 18, 0, 26, 0,

3, 0, 11, 0, 19, 0, 27, 0,

4, 0, 12, 0, 20, 0, 28, 0,

5, 0, 13, 0, 21, 0, 29, 0,

6, 0, 14, 0, 22, 0, 30, 0,

7, 0, 15, 0, 23, 0, 31, 0,

8, 0, 16, 0, 24, 0, 32, 0

]This mapping enables native byte-granularity extraction/splicing using a homomorphic partial trace. The partial trace is a composition of automorphisms which zero the first column of this matrix. By multiplying the ciphertext with \(X^{i}\) other columns can be zeroed.

FheUintPrepared

— control representation (GGSWs)A 32-bit word used as control (in arithmetic, branching, bit extraction, indexing…) is encoded as 32 GGSW ciphertexts:

\[ [\textsf{GGSW}(b_0), \ldots, \textsf{GGSW}(b_{31})]. \]

This format is used in evaluation of binary decision circuits, CMUXes, CSWAPs, blind rotations, etc, that are described below.

Phantom switches from the FheUint representation to

FheUintPrepared representation using circuit

bootstrapping (CBT) when an u32 in

loaded/stored/selected (GLWE) format needs to be used

as control (GGSW).

The CBT maps the encrypted bits of a GLWE (i.e. an

FheUint) to a set of GGSW (i.e. an

FheUintPrepared) encrypting a bit \(b\) to a GGSW ciphertext encrypting the

same bit:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m_{\textsf{u32}})\xrightarrow[\textsf{CBT}]{}[\textsf{GGSW}(m_0), \ldots, \textsf{GGSW}(m_{31})]. \]

GGSW is then be used in the external product operation, that we previously described. The external product is notably used to construct two important encrypted operations:

The CMUX, which enables the homomorphic selection between two GLWE, given a GGSW encrypting a control bit \(b\). \[\textsf{GLWE}(m_b)\leftarrow(\textsf{GLWE}(m_1) - \textsf{GLWE}(m_0)) \otimes \textsf{GGSW}(b) + \textsf{GLWE}(m_0)\]

The CSWAP, which enables the conditional homomorphic swap between two GLWE given a GGSW encrypting a control bit \(b\).

\[ \begin{align} \textsf{GLWE}(m_b) &\leftarrow (\textsf{GLWE}(m_1) - \textsf{GLWE}(m_0)) \otimes \textsf{GGSW}(b) + \textsf{GLWE}(m_0)\\ \textsf{GLWE}(m_{1-b})) &\leftarrow (\textsf{GLWE}(m_0) - \textsf{GLWE}(m_1)) \otimes \textsf{GGSW}(b) + \textsf{GLWE}(m_1) \end{align} \]

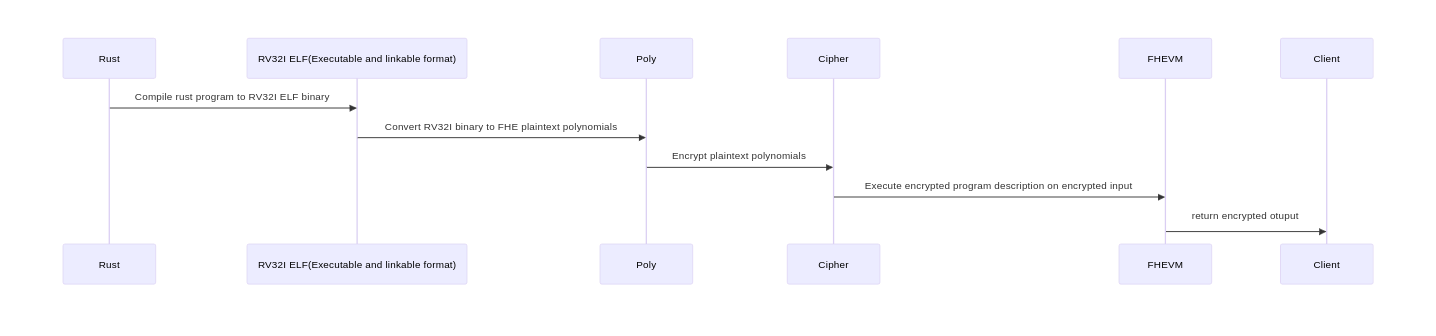

Following is a BDD of the most significant output bit (i.e. 2nd output bit) of two bit adder:

where a0,a1 are the bits of the first input and b0,b1 are the bits of the second input.

All nodes, except the ones at the last level are input nodes. To evaluate the 2 bit addition circuit, one traverses the BDD from top to bottom. At each node, if the bit value of the node is 0, branch to the child connected with the dotted arrow. Otherwise branch to the child connected with the solid arrow. Traverse until one of the terminal nodes (at the last level), the output bit, is reached.

Now if the two inputs, bits a0,a1,b0,b1, are encrypted, how will one traverse the BDD? The naive approach, from top to bottom, will double the no. of paths at every node, since both branches will have to be executed. This is a non-starter.

But what if one traverses the BDD bottom to top. Indeed, the output remains the same. But, notably, we avoid branching. Instead each node operation collapses (i.e. depending on its value, node selects either of its children) and at-most, K homomorphic selections are required.

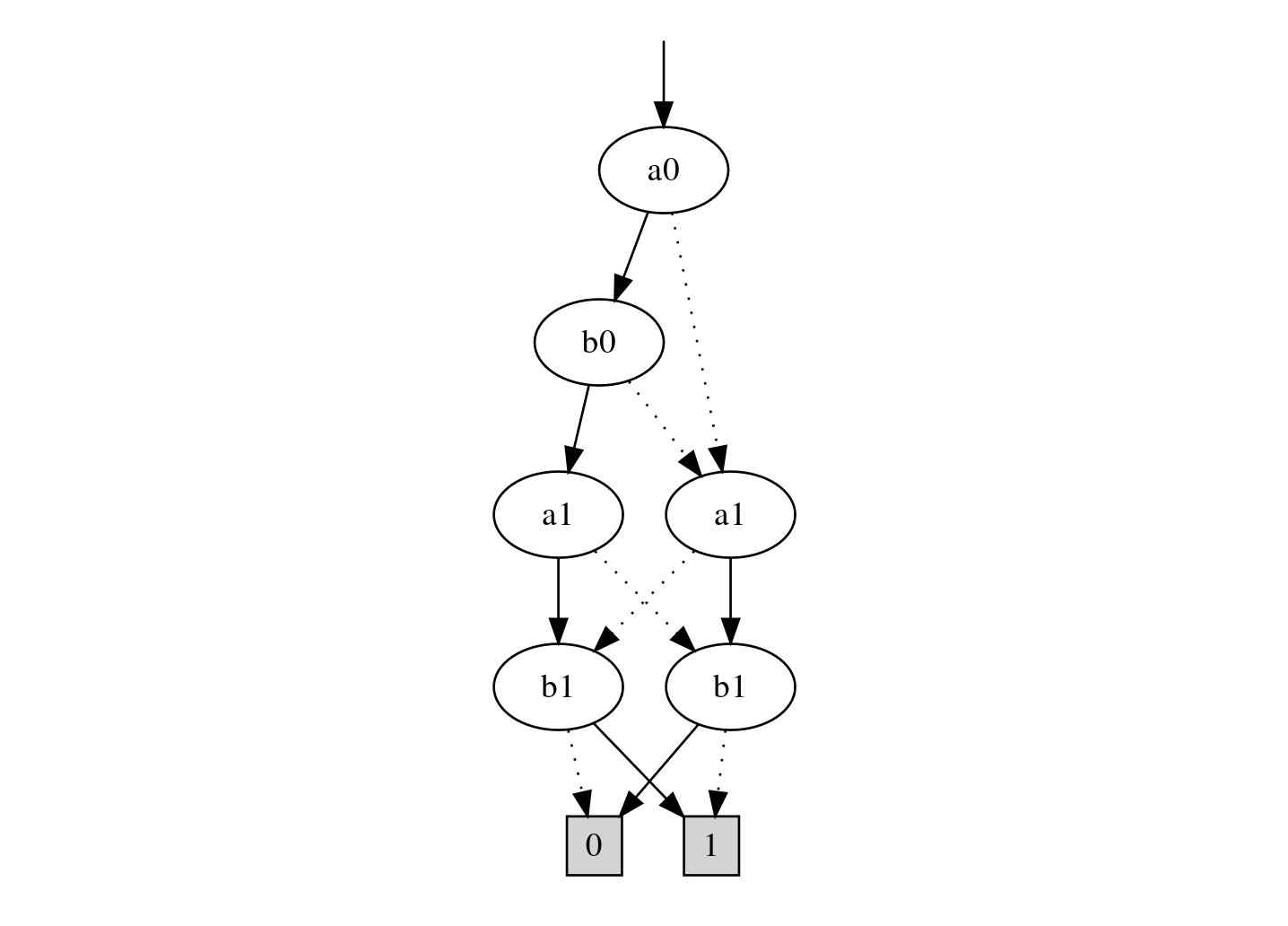

The diagram above is the 2-bit adder BDD, but inverted. Starting from the terminal nodes, we collapse the incoming edges per node (i.e. select the one labelled 0 if the node’s bit value is 0, otherwise select the one labelled 1) iteratively till the last node (i.e. the root node of BDD). The output is the output selected by the last node. We refer to an inverted BDD as the BDD circuit.

When input bits, a0,a1,b0,b1, are encrypted, each selection is implemented with CMUX:

\[\textsf{SELECT(b, x0, x1)} \rightarrow \textsf{CMUX(GGSW(b), GLWE(x0), GLWE(x1))}\]

where SELECT selects x0 if b equals 0, otherwise selects x1.

Usually the input bits are stored, packed, as a GLWE ciphertext (FHEUint), not GGSW ciphertexts. To execute a BDD circuit on an encrypted input, we unpack encryted bits and convert each bit to individual GGSW ciphertexts (i.e. FHEUintPrepared) via circuit bootstrapping (CBT).

\[\textsf{GLWE}(m_{\textsf{u32}})\xrightarrow[\textsf{CBT}]{}[\textsf{GGSW}(m_0), \ldots, \textsf{GGSW}(m_{31})].\]

All circuits for arithmetic/binary operations (e.g. add, sub, comparitors, and, etc.) on 32 bit inputs and PC update are implemented as BDD circuits. The source code of the circuits is available at this repository. The code autogens arithmetic/binary circuits for arbitrary bit-width (i.e. word size 32, 64, 128, 256, etc.) inputs and riscv compatible PC update. The codegen circuits are compatible with the poulpy FHE library.

The GGSW blind rotation by \(0\leq a < 2^{d}\) is defined as:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m) \cdot X^a \longrightarrow \textsf{GLWE}(m_a), \]

where the exponent \(a\) is

encrypted as an FheUintPrepared: \([\textsf{GGSW}(a_0), \dots,

\textsf{GGSW}(a_{31})]\).

Each encrypted bit \(a_i\) controls a rotation by \(X^{2^i}\) via a CMUX:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m\cdot X^{a_i2^{i}}) \leftarrow \textsf{CMUX}_{a_i}(\textsf{GGSW}(a_{i}), \textsf{GLWE}(m),\textsf{GLWE}(m)\cdot X^{2^{i}}) \]

Chaining all \(\lceil\log_{2}(d-1)\rceil\) conditional rotations yields a GLWE whose constant term is \(m_{a}\).

Blind retrieval is used to select which ciphertext to access in an encrypted array using an encrypted index — without revealing the index.

Phantom supports two variants:

| Variant | Used for | Operation | Allows write? | Mutates array? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stateless | faster read | CMUX tree | ❌ | ❌ |

| Stateful | read-modify-write | CSWAP network | ✔ | ✔ (internally) |

Using FheUint32Prepared index bits and \(0\leq n < 2^{d}\), a binary

CMUX tree selects:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m_0), \ldots, \textsf{GLWE}(m_{n-1}) \longrightarrow \textsf{GLWE}(m_a) \]

in \(\log_{2}(d-1)\) folding steps. The input array remains unchanged.

Since we have a bit-level encoding, we finish the selection by a GGSW Blind Rotation to move the desired bit into the first coefficient of the retrieved GLWE.

Encrypted CSWAPs reorders ciphertexts until:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(m_a) \text{ is moved to position 0}. \]

Similarly to stateless read, a GGSW Blind Rotation (which is also reversible) is used to move the desired bit into the first coefficient of the retrieved GLWE.

After reading or overwriting it, a reverse CSWAP sequence restores the initial encrypted ordering.

This enables encrypted memory writes at encrypted addresses.

Blind retrieval handles arrays. Phantom also supports encrypted selection from associative maps (hash maps) under encryption, without revealing the accessed key.

Given:

HashMap<u32, GLWE(value)>,FheUintPrepared,blind selection returns:

\[ \textsf{GLWE}(\text{map}[a]) \]

if the index \(a\) is not present in the map, GLWE(0) is returned.

The evaluator never learns:

Internally, blind selection uses CMUX to fold the hashmap, until only the index \(0\) remains.

Using GGSW Blind Rotations and GGSW Blind

Retrieval with an FheUintPrepared serving as

address, we can implement both read and write operations on the

encrypted memory.

Recall that it is structured as a \(32 \times \#\texttt{u32}\) matrix:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{0,0}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{0,N-1}]) & \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{0,N}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{0,2N-1}]) & \dots\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{31,0}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{31,N-1}]) & \textsf{GLWE}([\texttt{u32}_{31,N}, \dots, \texttt{u32}_{31,2N-1}]) & \dots\\ \end{bmatrix} \]

rs1,

rs2 and rd values are retrieved from the

REGISTERS. The stateless read is implemented by calling

a GLWE Stateless Blind Retrieval on each rows of the

matrix (one for each bit of the u32).u32 that is to be read are moved into the first coefficient

of the GLWEs of the first column of the matrix.In each case the retrieved the encrypted individual bits are

homomorphically packed into a single GLWE to produce an

FheUint.

| Goal | Building block |

|---|---|

interpret a u32 as data |

FheUint (GLWE) |

interpret a u32 as control |

FheUintPrepared (GGSW) |

| encrypted memory | \(32\times\#\texttt{u32}\) matrix of GLWE |

| circuit bootstrapping | FheUint -> FheUintPrepared |

| evaluate arithmetic, comparitors, branching circuits | Binary Decision Circuits (BDD) |

select a bit inside an FheUint |

GGSW Blind Rotation |

select an FheUint in an encrypted array |

GGSW Blind Retrieval |

select an FheUint in an encrypted associative map |

GGSW Blind Selection |

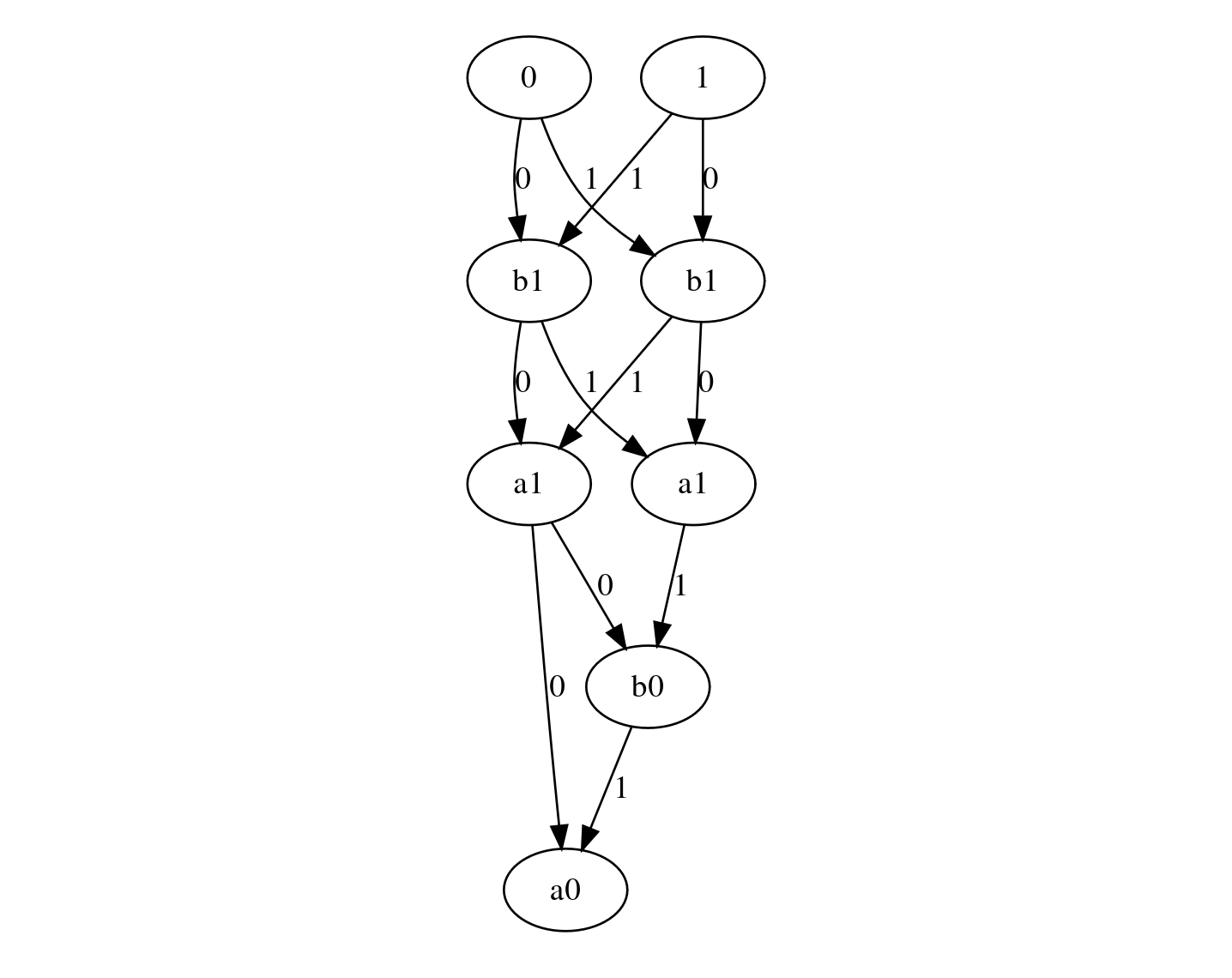

You’ll find hereunder a detailed dataflow diagram illustrating how each components of the encrypted VM:

interact with each others.

Click for enlarged image

Benchmarks were obtain with an r6i.metal using 32 cores.

The ROM and RAM size each of 0.4KB (9 bits PC) and 4KB (12 bits addresses) respectively.

In hardware, registers sit next to the processor (i.e. where actual operation happens). Hence, reading from registers is extremely fast. Whereas RAM accesses are orders of magnitude slower.↩︎

In rv32i, all instructions, except 2, either only mutate Registers, or PC, or the RAM. Only JAL, JALR mutate both PC and Registers.↩︎